‘There was no oversight’: NH child advocate has been a watchdog for children's care. Now, the office is on the chopping block

Cassandra Sanchez hadn’t left the parking lot before she hit send on the email.

New Healthy Buffalo owner to build market in Chichester

Jason McKay jokes with friends that Chichester is the greatest place on Earth, but laughs aside, he loves his hometown. In August, McKay took over the Healthy Buffalo, a longstanding local meat shop, and he now intends to open a market next spring. McKay also plans to move the Healthy Buffalo, which has been a staple business in town for over 30 years, to the new market location on Dover Road by Speedway.

Most Read

Casella Waste Systems’ landfill project in New Hampshire’s North Country denied permit

Casella Waste Systems’ landfill project in New Hampshire’s North Country denied permit

‘Less finger pointing, more communication’: Longtime Chichester residents share hopes before second town meeting

‘Less finger pointing, more communication’: Longtime Chichester residents share hopes before second town meeting

‘The revenue just isn’t there’: House Finance Committee slashes $271M in jobs, services from Ayotte’s budget proposal

‘The revenue just isn’t there’: House Finance Committee slashes $271M in jobs, services from Ayotte’s budget proposal

12 Concord student-athletes sign on to play at the collegiate level

12 Concord student-athletes sign on to play at the collegiate level

‘There was no oversight’: NH child advocate has been a watchdog for children's care. Now, the office is on the chopping block

‘There was no oversight’: NH child advocate has been a watchdog for children's care. Now, the office is on the chopping block

Volunteer group wants to help homeless clean up their camp

Volunteer group wants to help homeless clean up their camp

Editors Picks

The Monitor’s guide to the New Hampshire legislature

The Monitor’s guide to the New Hampshire legislature

‘That wasn’t the charge we were given’ – New city councilors question golf clubhouse options

‘That wasn’t the charge we were given’ – New city councilors question golf clubhouse options

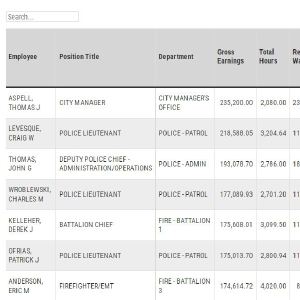

Sunshine Week: Searchable database of what Concord city employees were paid in 2024

Sunshine Week: Searchable database of what Concord city employees were paid in 2024

Immigrants in New Hampshire face uncertainty as temporary protections expire soon

Immigrants in New Hampshire face uncertainty as temporary protections expire soon

Sports

Concord’s USA Ninja Challenge aligned with changes to Pentathlon before LA 2028 Olympics

When Concord entrepreneur Dale Grant was first approached with the idea of creating a “Ninja Challenge” gym over a decade ago, he had no idea where the venture would end up.

Monitor names winter 2024-25 Players of the Season

Monitor names winter 2024-25 Players of the Season

Boys’ basketball: Pembroke tops Sanborn to claim D-II state title

Boys’ basketball: Pembroke tops Sanborn to claim D-II state title

Opinion

Karishma Manzur, Ph.D. is a science writer living in Exeter. She volunteers with various groups, including the New Hampshire Coalition for a Just Peace in the Middle East, which includes state chapters of Veterans for Peace, Jewish Voice for Peace, Peace Action and several other organizations.

Opinion: Courage and care count

Opinion: Courage and care count

Opinion: What rough beast is slouching toward us to be born

Opinion: What rough beast is slouching toward us to be born

Opinion: The special education gimmick in NH school voucher rules

Opinion: The special education gimmick in NH school voucher rules

Opinion: What Trump really means by government efficiency

Opinion: What Trump really means by government efficiency

Your Daily Puzzles

An approachable redesign to a classic. Explore our "hints."

A quick daily flip. Finally, someone cracked the code on digital jigsaw puzzles.

Chess but with chaos: Every day is a unique, wacky board.

Word search but as a strategy game. Clearing the board feels really good.

Align the letters in just the right way to spell a word. And then more words.

Politics

Town elections offer preview of citizenship voting rules being considered nationwide

A voter in Milford, New Hampshire, missed out on approving the town’s $19 million operating budget, electing a cemetery trustee and buying a new dump truck. In Durham, an 18-year-old high school student did not get a say in who should serve on the school board or whether $125,000 should go toward replacing artificial turf on athletic fields.

Medical aid in dying, education funding, transgender issues: What to look for in the State House this week

Medical aid in dying, education funding, transgender issues: What to look for in the State House this week

On the Trail: Shaheen’s retirement sparks a competitive NH Senate race

On the Trail: Shaheen’s retirement sparks a competitive NH Senate race

‘If it affects one, it’s going to affect all’: Dozens protest federal firings in Concord

‘If it affects one, it’s going to affect all’: Dozens protest federal firings in Concord

On the Trail: Window closing on Shaheen decision to run in 2026

On the Trail: Window closing on Shaheen decision to run in 2026

Arts & Life

Evolution Expo bringing wellness to Concord this weekend

The highly anticipated 5th Evolution Expo is set to take place on Sunday, April 6, 2025, at the Grappone Conference Center in Concord. Hosted by Holistic Pros, this event is dedicated to empowering individuals with alternative and complementary care options.

Around Concord: Cali Arepa brings ‘a little bit of Colombia’ to the Capital Region

Around Concord: Cali Arepa brings ‘a little bit of Colombia’ to the Capital Region

Around Concord: On-stage dynamite, LEE & DR. G are ‘stunningly live’

Around Concord: On-stage dynamite, LEE & DR. G are ‘stunningly live’

Obituaries

Pamela Gilchrist Munnell

Pamela Gilchrist Munnell

[IMAGE]Pamela Gilchrist Munnell Concord, NH - Pamela Gilchrist Munnell, 61, passed away peacefully on March 26, 2025, surrounded by her loving family. Pam grew up in Wellesley MA where she graduated from Dana Hall and then graduated from... remainder of obit for Pamela Gilchrist Munnell

Cynthia Charlotte Mitchell

Cynthia Charlotte Mitchell

Cynthia Charlotte (Cass) Mitchell Concord, NH - Cynthia Charlotte (Cass) Mitchell passed away on Monday, March 31, 2025 at the age of 96. She was born in Concord, N.H. on October 25, 1928, the daughter of the late Ellery E. Cass and Emm... remainder of obit for Cynthia Charlotte Mitchell

Jean M. Crouch

Jean M. Crouch

Penacook, NH - Jean M. Crouch, age 70, of Borough Road passed away unexpectedly on Thursday, March 27, 2025 at Elliot Hospital in Manchester. Jean dedicated her life to helping others, a champion for countless causes, her contributi... remainder of obit for Jean M. Crouch

Thomas Moore Celebration of Life

Thomas Moore Celebration of Life

Thomas (Tucker) Moore Celebration of Life Concord, NH - Sunday, May 11. 2025. 1-4 pm. The Broken Tee Restaurant at Beaver Meadow Golf Club, Concord, NH. All who knew Tom (Tucker) are invited to attend this remembrance and tribute to his... remainder of obit for Thomas Moore Celebration of Life

Ayotte crusaded against a ‘broken’ bail system. Defense lawyers say it worked just fine

Ayotte crusaded against a ‘broken’ bail system. Defense lawyers say it worked just fine

Does New Hampshire still need the Housing Appeals Board?

Does New Hampshire still need the Housing Appeals Board?

High school track previews: Concord looks to build off of record-breaking season

High school track previews: Concord looks to build off of record-breaking season

Comics in Concord: Old School Comic Show bringing hundreds to Everett Arena

Comics in Concord: Old School Comic Show bringing hundreds to Everett Arena

Margaritas in Concord holding 40th anniversary bash

Margaritas in Concord holding 40th anniversary bash

Boys’ hockey: Concord takes championship in historic quadruple overtime victory over BG, 2-1

Boys’ hockey: Concord takes championship in historic quadruple overtime victory over BG, 2-1 Ex-Celtic Enes Kanter Freedom speaks in NH on human rights advocacy

Ex-Celtic Enes Kanter Freedom speaks in NH on human rights advocacy Bow High School senior Albushies wins first place, headed to semifinals in 4-Way Speech Contest

Bow High School senior Albushies wins first place, headed to semifinals in 4-Way Speech Contest Around Concord: Eagle Pond Farm, its literary inhabitants, and the nonprofit preserving their legacy

Around Concord: Eagle Pond Farm, its literary inhabitants, and the nonprofit preserving their legacy