Does New Hampshire still need the Housing Appeals Board?

| Published: 04-04-2025 4:16 PM |

A Manchester apartment building burned down, and its new owner was looking to rebuild; a Meredith duplex owner wanted to add another unit; a developer wanted to build 65 market-rate apartments in Pelham.

After local boards voted down their applications, they asked the New Hampshire Housing Appeals Board to for a second opinion, and found relief. The board found that local officials had ruled unreasonably, lacked justification for their decision, or didn’t give the applicant a way to get conditional approval.

Lawmakers created the Housing Appeals Board in 2020 to speed up the process of challenging the decisions of local zoning and planning boards. The idea was that it would benefit everyone — towns, taxpayers and builders alike — to create new and faster ways to resolve housing project disputes.

Housing and development advocates say it has delivered.

“When we talk to developers, they really think it’s a great addition to the process and has done exactly what it was meant to do,” said Nick Taylor, director at New Hampshire Housing Action. “It’s fair and it’s quick, and it’s a much better way, in their opinion, than going through the Superior Court process.”

The board began hearing cases as state leaders said they wanted to prioritize the construction of more housing.

“Time is really one of the singular issues that would impact and lead to housing projects not making it through the development process… if something takes months or years to get approved, your financing and your economic modeling behind it doesn’t make sense anymore,” said Mike Skelton, president of the Business and Industry Association of New Hampshire. “I think the housing appeals board was developed and created with that in mind and, in our view, it’s been a great success.”

House lawmakers, though, have proposed eliminating the appeals board, saying it doesn’t handle enough cases to be worth its roughly $575,000 price tag in the state budget. Unlike many other cuts put forward by House Republicans, it has so far won support from some Democrats, too.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

After four decades collecting carts, Ricky Tewksbury will retire when Shaw’s closes mid-April

After four decades collecting carts, Ricky Tewksbury will retire when Shaw’s closes mid-April

Written shooting threat sends Concord High students home early

Written shooting threat sends Concord High students home early

‘It’s everything’: In largest rally yet, Trump protestors descend on Concord

‘It’s everything’: In largest rally yet, Trump protestors descend on Concord

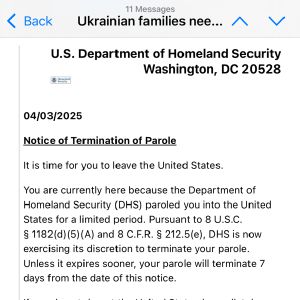

DHS email error causes stress, anxiety for New Hampshire's Ukrainian community

DHS email error causes stress, anxiety for New Hampshire's Ukrainian community

‘There was no oversight’: NH child advocate has been a watchdog for children's care. Now, the office is on the chopping block

‘There was no oversight’: NH child advocate has been a watchdog for children's care. Now, the office is on the chopping block

“There’s a number of boards that we’re getting rid of, not because they’re doing a bad job but because they’re not cost effective at that job,” said Rep. Dan McGuire, an Epsom Republican, presenting amendments to the House Finance Committee. “It’s sort of a nice-to-have, not a must-have.”

Before the appeals board was created, anyone wanting to fight local decisions about a housing approval had to go to court. Especially with a pandemic backlog and the priority given by criminal cases, housing projects can get bogged down by delays.

The Housing Appeals Board, as a panel of three experts, was crafted to be faster, more affordable, and more user-friendly to the average resident. The state has used this quasi-judicial model for other types of legal conflicts, from the Right to Know law to property tax appeals. Other New England states, including Massachusetts and Rhode Island, have similar boards, and housing advocates in Maine have been pushing for the state to create one based on New Hampshire’s model.

Among the roughly 30 cases per year filed with the board, 14% of applicants have represented themselves, according the board’clerk Elizabeth Menard.

When it came to state attempts to address the housing crisis, the appeals board threaded the line between local control and state action. The board reviews whether local officials applied their own rules correctly, helping to untie the knots of some local regulation enforcement. But it leaves local rules intact, making it less heavy-handed than statewide zoning mandates.

“There was a concern that, now you’ve got some state agency who knows it all, and they’re going to tell the local people to go pound sand,” said David Rogers, the board’s chair. “We’re not substituting our judgment for the local boards, we’re trying to make it clear to people that the rules are there to be followed, that it’s not just a gut feeling you have.”

Laura Spector-Morgan, an attorney who’s represented half a dozen towns and cities in housing appeals board cases, spoke positively of the board’s members, and noted that initial concerns from local officials that the board would be developer-friendly haven’t borne out.

“I have found them knowledgeable, I have found them prepared, and I have found them fair,” Spector-Morgan said.

However, she continued, some of her clients have had issues with the board’s pace, which she said can be slower than the courts.

“The only concern I have heard, and I have heard it mostly from the applicants, is that they have not been issuing decisions in a particularly timely manner,” Spector-Morgan said. “I am waiting, at times, nine months for decisions out of the housing appeals board.”

In a typical case before Judge Michael Klass, Spector-Morgan said, a decision is issued within two months of a hearing. The appeals board is legally required to follow a similar timeline, but that’s frequently not happening with her clients, she said.

From filing to a final decision, the appeals board process, on average, takes just over 5 months, according to Menard, the clerk.

There are exceptions: The appeals board website lists its pending cases, which includes some dating back to 2023. Sixteen of them had hearings before the start of this year.

These longer timelines can have a number of causes, Menard noted: either side in a case can request longer windows to file things or to continue a hearing, just like in court. Maybe that’s to take time to negotiate, maybe its because of an attorney’s illness. Last year, two simultaneous vacancies took months to fill, which led to hold-ups.

This isn’t the first time lawmakers have tried to cut, limit or consolidate the appeals board. But this year is different.

The state is staring down the barrel of major revenue shortfalls, and agency cuts in the name of government efficiency are one way House budget writers are looking to reduce spending.

There’s also the addition of the land use docket — a specific judge in superior court designated for these kinds of appeals to help move things along. Judge Klass, once a member of the appeals board, was appointed in January 2024. Like the appeals board, the docket is required to follow an accelerated timeline.

Looking at both overall case volume and a cost-per-case basis, McGuire has argued, a land use judge does more for less.

“I’m not aware that the cost of housing in New Hampshire has declined in particular as a result of the Housing Appeals Board,” he said. “How could it if it only does 30 cases a year?”

If their caseload — as well as that of the Board of Tax and Land Appeals, also proposed to be cut — were funneled into Klass’ docket, it could create a backlog. Klass also presides over non-land use issues, which critics of the cuts worry could sideline housing cases over time.

New Hampshire Housing Action’s Taylor shared this concern. While the land use docket was a positive addition to the process, he said, it’s not clear what its capacity limits are. Having a dedicated path through the Housing Appeals Board ensures those cases don’t take a backseat.

Court records show slightly more than half of the cases assigned to Klass, including 11 of 20 filed this year, have been zoning or planning board appeals.

If the state added more judges to relieve that, overall spending would be about equal, appeals board members noted.

“It’s a cost shifting, not really a savings,” David Rogers said. “You’d just be moving costs from one branch to the other.”

The House of Representatives is expected to review the $16.3 billion two-year state budget next week before sending it to the state Senate.

A spokesperson for the state court system declined the Monitor’s request to interview Klass and did not respond to further inquiry about court capacity if the appeals board were eliminated.

Proponents also see the board’s benefits as going beyond just its caseload.

The thoroughness of the board’s written decisions and its responsiveness, Skelton said, has created a stronger incentive for towns and builders to reach a solution at the local level.

Ed Rogers, an engineer on the appeals board, has seen that in action.

“I’ve definitely noticed over the last four years, in local meetings that I’ve attended, a greater seriousness,” he said. “Boards really intent on taking cases more seriously, trying to make good decisions, because they know there is this alternative for landowners that don’t feel like they got a fair shake.”

Rogers, no relation to the board chair, also worries that absorbing their caseload back into the court system would close the door on some projects. While the land use docket may be changing things, a perception exists among homeowners and developers alike that court is long, arduous and expensive. The appeals board is more approachable.

“We have people who are coming to the housing appeals board or the Board of Tax and Land Appeals who are not going to go to the superior court,” he said. “So you will have a chilling effect where people aren’t utilizing the system to get relief when they would use these smaller boards.”

If state zoning reforms — which are gaining greater traction this year — are implemented, appeals board members and proponents think its role would become more important than ever.

“Each one of these levers that we’re pulling, and barriers that go into the development process that have to be worked on… they need to come together,” Taylor said. “If you still have one that’s a major barrier, you’re not going to be able to reach the housing numbers that we need and the housing options that folks in New Hampshire desperately need.”

The state’s housing finance authority estimates New Hampshire could use 90,000 more housing units by 2040.

“This is not going away anytime soon,” Skelton said. “So I think we would be really hurting our ability to adequately address this if we’re taking things like the housing appeals board off the table right in the middle of when we’re, as a state, starting to take some good steps forward.”

Having both the land use docket and the appeals board as options for landowners, he said, is a good thing.

“This is not a time to be taking any tools out of the toolbox.”

Catherine McLaughlin can be reached at cmclaughlin@cmonitor.com. You can subscribe to her Concord newsletter The City Beat at concordmonitor.com.

Henniker ponders what is a ‘need’ and what is a ‘want’

Henniker ponders what is a ‘need’ and what is a ‘want’ Boscawen residents vote to fund major renovation of public works building

Boscawen residents vote to fund major renovation of public works building ‘Voting our wallets’: Loudon residents vote overwhelmingly against $1.7M bond for new fire truck

‘Voting our wallets’: Loudon residents vote overwhelmingly against $1.7M bond for new fire truck In Pembroke, Education Freedom Accounts draw debate, voters pass budget

In Pembroke, Education Freedom Accounts draw debate, voters pass budget