Grace Mattern: The importance of recognizing white privilege

| Published: 10-19-2017 12:15 AM |

The last time you handled a challenge well, were you called a credit to your race? When you go shopping, do store clerks watch you closely or follow you? Do you have trouble finding a hair salon nearby that knows how to style your hair? When you buy greeting cards and magazines, is it difficult to find ones with people the same race as you?

If you answered no to these questions, you’re almost certainly white. There’s also a good chance you’ve never looked at your whiteness this way.

Whiteness is the default norm around which most of our culture is organized, and because it permeates our world without being acknowledged, it’s largely invisible.

I’d never thought about white privilege and the advantages it’s given my family and me until I read White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack by Peggy McIntosh.

McIntosh poses the questions above and others that illustrate how the lives of white people are made easier, safer and more comfortable by the simple fact of their skin color. If you think about the questions in the reverse, you see how many challenges black and brown people face as they navigate daily life.

The power of white privilege comes in part from how it’s woven into our lives so we don’t notice it.

In New Hampshire it’s particularly invisible, given that 94 percent of the state’s population is white. That doesn’t mean white privilege, and the resulting discrimination of people of color, isn’t an issue for our state. If you’re white, you carry that privilege with you wherever you go. You benefit from the assumption of whiteness as the norm no matter where you live.

White people can be defensive about the idea that they have any special privilege. What about the disadvantages people encounter due to poverty, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation and all the other facets of people used to judge them negatively?

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

After four decades collecting carts, Ricky Tewksbury will retire when Shaw’s closes mid-April

After four decades collecting carts, Ricky Tewksbury will retire when Shaw’s closes mid-April

Written shooting threat sends Concord High students home early

Written shooting threat sends Concord High students home early

‘It’s everything’: In largest rally yet, Trump protestors descend on Concord

‘It’s everything’: In largest rally yet, Trump protestors descend on Concord

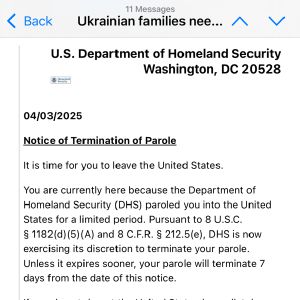

DHS email error causes stress, anxiety for New Hampshire's Ukrainian community

DHS email error causes stress, anxiety for New Hampshire's Ukrainian community

‘There was no oversight’: NH child advocate has been a watchdog for children's care. Now, the office is on the chopping block

‘There was no oversight’: NH child advocate has been a watchdog for children's care. Now, the office is on the chopping block

That’s not the point. Acknowledging white privilege doesn’t negate other forms of discrimination. Rather, it’s a way to recognize that people of color in our country have more difficult lives because white skin is privileged and dark skin isn’t. It doesn’t mean some white people don’t encounter discrimination for a whole host of reasons.

As the only Jewish students in their elementary school, my children had to deal with anti-Semitic comments. But when they walk through the world, the negative attitudes and myths that have collected around having dark skin don’t affect them. People of color never have that privilege.

Our country’s history of institutionalizing discrimination against people of color is an important building block in the construction of whiteness as the norm. The most blatant example from our history is slavery, but many people look at that as a crime our country needs to move past.

There are plenty of more recent examples.

In the mid-20th century, the Federal Housing Administration helped millions of average-income Americans buy homes for the first time. White Americans. The federal government developed a neighborhood appraisal system that tied mortgage eligibility to race. In a practice now known as “redlining,” integrated communities were considered riskier for home loans and thus ineligible.

Of the $120 billion of government-backed home loans made between 1934 and 1962, more than 98 percent went to whites.

When the Social Security Act of 1935 was enacted, its aim of providing a safety net for millions of workers by guaranteeing them an income after retirement benefited white people more uniformly than people of color. Two occupations that were excluded from the act, agricultural workers and domestic servants, employed 65 percent of black workers at the time. The exclusions weren’t removed until the 1950s.

Unions were granted the power of collective bargaining by the 1935 Wagner Act, which led to increased wages, helping to create a financially secure middle class over the next 30 years. The Wagner Act was one more leg up for white workers. Unions were permitted to exclude non-whites. Some craft unions remained nearly all-white well into the 1970s.

These policies directly contributed to the disparity between the net worth of black and white households in the U.S. Whites have a median household worth that’s 10 times that of blacks, and the gap has widened over the past several years.

Home ownership, retirement savings and educational debt all contribute to the inequity. Tax policies that favor homeowners and people with retirement accounts help lock in place the advantages that benefit wealthier, mostly white Americans. The result is that far fewer black families are able to pass on assets to their children, which helps keep the system of white privilege in place.

Our country’s legacy of privileging white skin and discriminating against people of color continues.

In May 2016, a federal appeals court overturned changes to North Carolina’s voting process, ruling that the new law was passed with “discriminatory intent” and designed to make it more difficult for black people to vote. The court’s opinion stated that the law appeared to “target African Americans with almost surgical precision.”

This past August a federal judge struck down a Texas voter ID law she said was enacted with an intent to discriminate against black and Hispanic voters.

Voter suppression efforts don’t exclusively target black and brown people, but they don’t target people solely because they’re white.

Acknowledging white privilege doesn’t mean you have to feel guilty or consider yourself racist. Recognizing how white skin protects you from discrimination is a first step in breaking down an invisible and insidious underpinning of racial inequity.

(Grace Mattern is a poet and writer who lives in Northwood. She blogs at gracemattern.com.)

]]>

Opinion: Courage and care count

Opinion: Courage and care count