From the archives: The little-known Londonderry Riot

A February 1769 letter from Royal Governor of New Hampshire John Wentworth to General Thomas Gage regarding the Londonderry Riot. Courtesy

| Published: 01-07-2024 6:00 AM |

Tensions were high in colonial New Hampshire. A Portsmouth mob had forced the resignation of a British tax collector, the Townsend Acts were being debated among the colonies, disputes over New England timber were coming to a head, and discussions of taxation without representation were frequent.

The major issue for the British army was soldier desertion. Many young men from the ranks found the pay low and the discipline harsh. Away from big, coastal cities, it was relatively easy to escape in the new world. Londonderry was a vast land that then included present-day Derry and housed 2,590 colonists.

In early January 1769, a group of deserters (there is debate over the exact number) were living in Londonderry. It is unknown how the British army was informed of their presence, though local patriots suspected judge and tavern owner, Stephen Holland, of harboring Tory sympathies. A detachment of regulars was quickly sent to recover the deserters, the punishment for which was hanging. The prisoners were marched out of town.

Word immediately got out, and eleven men from the town, some veterans of the French and Indian War, chased down the British to free the deserters. With guns drawn, the Londonderry men surprised the British, who by then were in the town of Atkinson, and managed to escape with the prisoners back to town without bloodshed.

Governor John Wentworth at first tried to deny that such a thing would happen in New Hampshire, insisting to Colonel John Pomeroy of his majesty’s 6th regiment that the incident must have occurred in Massachusetts Bay. Upon receiving word that the incident did, in fact, occur here, Wentworth wrote to General Thomas Gage, Commander-in-Chief of the British Army in North America, to assure him that “the utmost care and diligence shall be exerted to discover and bring to punishment the rioters who rescued the deserters near Londonderry.”

Wentworth likely felt personally betrayed by these actions. When he became royal governor in 1767, he had received a proclamation of love and loyalty from the town’s selectmen.

In a February 4, 1769 letter to Colonel Edward Goldstone Lutwycke, Wentworth laments, “It has been represented to me by the generals of his majesty’s troops, that many deserters from them, are and have been harbored and concealed within this province which is a great seducement to the soldiers, who at all times are too easy to be seduced from their duty; this conduct in open violation of the law, abounds in fatal consequences to the king’s service, and is still more injurious to the province in bringing a reproach upon our law and loyalty, filling the country with miscreants who, let loose from the only discipline that can restrain them, will soon scatter every kind of mischief, villainy, and rapine through all our towns.”

On March 23, Wentworth issued a proclamation which was distributed to every town in New Hampshire, warning against “harboring and entertaining” deserters. Despite this, the Londonderry rioters were never punished; there is no evidence that they were ever charged for their crimes. As for the deserters, Wentworth argued for leniency, insisting they be let back into the army, but very few were caught. Wentworth later claimed that all deserters must have moved on to other colonies.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

After four decades collecting carts, Ricky Tewksbury will retire when Shaw’s closes mid-April

After four decades collecting carts, Ricky Tewksbury will retire when Shaw’s closes mid-April

Written shooting threat sends Concord High students home early

Written shooting threat sends Concord High students home early

‘It’s everything’: In largest rally yet, Trump protestors descend on Concord

‘It’s everything’: In largest rally yet, Trump protestors descend on Concord

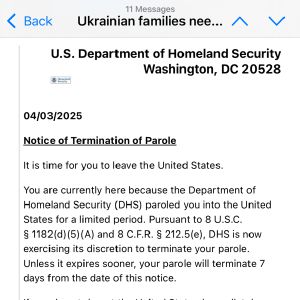

DHS email error causes stress, anxiety for New Hampshire's Ukrainian community

DHS email error causes stress, anxiety for New Hampshire's Ukrainian community

‘There was no oversight’: NH child advocate has been a watchdog for children's care. Now, the office is on the chopping block

‘There was no oversight’: NH child advocate has been a watchdog for children's care. Now, the office is on the chopping block

Though small, the Londonderry Riot shows the impact a few brave individuals can have. In the face of overwhelming odds and threats of death, the eleven Londonderry men did what they thought was right.

From the Archives is a monthly column highlighting the history and collection of the New Hampshire State Archives, written by Ashley Miller, New Hampshire State Archivist. Miller studied history as an undergraduate at Penn State University and has a master’s degree in history and a master’s degree in archival management from Simmons College.

Henniker ponders what is a ‘need’ and what is a ‘want’

Henniker ponders what is a ‘need’ and what is a ‘want’ Boscawen residents vote to fund major renovation of public works building

Boscawen residents vote to fund major renovation of public works building ‘Voting our wallets’: Loudon residents vote overwhelmingly against $1.7M bond for new fire truck

‘Voting our wallets’: Loudon residents vote overwhelmingly against $1.7M bond for new fire truck In Pembroke, Education Freedom Accounts draw debate, voters pass budget

In Pembroke, Education Freedom Accounts draw debate, voters pass budget