Dandelion Hill, Pt. 3: Determining the winner of the land-tending contest

| Published: 10-21-2023 4:00 PM |

In the last year of the contest, Eartha paid particularly close attention to the land she had given Abel, Beau, and Carson.

Abel was long gone from his land. After he ran out of money, he had left the area to take a job to support himself. When he left, his land was a muddy lifeless mess. But in the time since Abel had left his land, the land had started to come back to life. No longer was it a soupy mudhole.

Grass seeds and flower seeds and tree seeds had been blown in on the wind. More seeds found their way to Abel’s land when birds flew over it and pooped and four-legged animals ran across it and pooped. Some of those seeds worked their way into the ground. Some of the seeds sprouted. Some of the sprouts grew up into grasses and wildflowers and saplings that started sprouting seeds of their own.

When flowers started blossoming on Abel’s land, bees began buzzing by to pollinate them and help them extend their territory.

When the new plants took root, they helped hold the soil in place. With the soil firmly in place, rainwater could find its way across Abel’s land in cool clear streams. With the plants and clear water, a few small animals returned to Abel’s land.

As Eartha scanned Abel’s land, she knew that he would not win the contest because he had not done the best with his land. But she was rather amazed by what Mother Nature had done with Abel’s land after he had done so poorly with it.

As for Beau, Eartha was certain that he would be the winner of her contest. He hadn’t torn up his land. He had worked very hard, and had made his land perfectly beautiful. But oddly, even surrounded by all the beauty of his perfectly ordered park, Beau didn’t seem all that happy. There were the dandelions every spring that Beau dug up and tossed aside.

Beau also had other frustrations. He was troubled by the animals on his land, the deer and the rabbits and the chipmunks who nibbled on his flowers and burrowed into his flower beds to make homes for their families. He used some of the money he collected from admissions to build miles and miles of fences to keep the animals out of his gardens. But the animals who loved Beau’s gardens found ways to get over his fences, or through them, or under them.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

When the fences didn’t work, Beau hired trappers to gently capture the deer and the rabbits and the chipmunks and relocate them far away from his gardens. He was dismayed to find that as soon as the trappers left, the animals came back. He thought about taking more drastic steps, like buying poison or hiring hunters, but he didn’t like the way those thoughts made him feel. He felt like he was stuck between a rock and a hard place.

Beyond that, when people visited Beau’s land, he fretted whenever a blossom was a little droopy, whenever a sparkly new spider’s web appeared on a rosebush, or whenever a leaf had a hole in it, left by a hungry bug who had stopped by for a bite to eat. In addition to worrying about the state of his plants, Beau became cross whenever a visitor left one of his gravel pathways to get a different view from the view that he had intended.

Worst of all was the picture book. When Beau went to work in the gardens in his park, he carried an album he had made out of photographs he had taken one day, four or five years ago, when he had decided that his gardens were perfectly complete and exactly to his liking.

Ever since that day, Beau’s work on his land consisted of nothing more than toiling away to make his gardens look just like the pictures in his book. Beau could usually come pretty close, but his gardens were never exactly perfect again, and Beau was never exactly happy when he was on his land.

While Eartha was greatly impressed with what Beau had done with his land, she began to worry that if she gave all of her land to Beau, he would be overwhelmed by all the things he could not control, all the things that would never be quite perfect.

Carson was another story. Carson seemed to love the unexpected. She made a note whenever she saw a kind of plant she had never seen before, whenever she encountered a species of animal she had never encountered before, or whenever she heard a birdsong she had never heard before. She was always delighted to learn something new about her land.

Carson had plenty of time to explore her land as she tended to her crops. She collected baskets and baskets of dandelion greens that she sold to restaurants for salads. In the cool of the morning, she collected mushrooms that people prized for their rich wild flavor and firm meaty texture. She had several stands of sunflowers that she shared with the birds, one head full of seeds for them, one for her. She collected honey from hives that she had built from lumber cut from trees that had been blown down by storms.

And she had gardens, dozens of them tucked away here and there on her land. She picked the spots that were best suited to each sort of vegetable and fertilized her gardens with the manure she got from the dairy farm down the road. In each garden, Carson always planted enough for her to eat, plus a little bit more to sell to her neighbors, plus a little bit more for the animals to eat.

Carson was happy to live on her land, and the land was happy to have her. She was always able to get everything she needed from her land, plus a little bit more, from selling salad greens and mushrooms, carrots and potatoes and cabbages, parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme, and all sorts of other fresh garden produce.

In fact, when an especially attractive piece of land right next to Carson’s land came up for sale, Carson was able to buy it with the profits she had earned from selling her crops. After seeing how well Carson had treated her land, and how well the land had treated Carson, Eartha knew that Carson was the winner of her contest.

Eartha let Abel and Beau keep the land she had given them to tend, but she gave all the rest of her land to Carson, with the hope that Carson would find other people like her to live with her on her acres and acres and acres of land, land in the North, land in the South, land in the East, and land in the West.

Normally, at this point in a story, the storybook says: THE END

but because there’s a little bit of Carson in all of us, and a little bit more if we just try hard enough, this story ends by saying: THE BEGINNING.

Parker Potter is a former archaeologist and historian, and a retired lawyer. He is currently a semi-professional dog walker who lives and works in Contoocook. His work usually appears in the Opinion section. This is his first intentional foray into writing fiction.

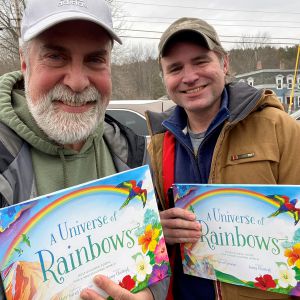

“A Universe of Rainbows”: Warner author releases children’s poetry anthology

“A Universe of Rainbows”: Warner author releases children’s poetry anthology  Comics in Concord: Old School Comic Show bringing hundreds to Everett Arena

Comics in Concord: Old School Comic Show bringing hundreds to Everett Arena Margaritas in Concord holding 40th anniversary bash

Margaritas in Concord holding 40th anniversary bash Evolution Expo bringing wellness to Concord this weekend

Evolution Expo bringing wellness to Concord this weekend