Tragedy decades ago in Boscawen serves as a reminder to students: don't drink and drive

| Published: 05-21-2023 2:00 PM |

Lynn Colby wants high school students to remember that it’s not too late to avoid a catastrophe that will forever alter the course of many lives.

It altered Colby’s. Her brother, Skipper Kingsbury, got drunk and drove into a tree three days before graduating from Merrimack Valley High School, breaking his neck and dying within minutes of the crash. It happened on June 13, 1975, and even after all these years, it hasn’t faded from Colby’s mind.

That’s why Colby wants people to listen to her. Enjoy the corsages, the music, the dancing, the friendships, the celebrations, all of which will be featured after proms and graduations across the state this month and next. Live it up, Colby says, but make sure you live.

Make sure you hear the speeches at graduation and toss your cap in the air with your classmates.

Enjoy getting dressed up for prom, and then the summer nights, when school is over.

But please, please, please, don’t drink and drive, Colby says. It can kill the driver as well as the passengers in the car. More to her point, Colby says these deadly crashes leave families scarred forever, wondering if they had emphasized the dangers of drinking and driving enough to keep their children safe.

“My dad cried and I still cry,” Colby said. “He was so sad, and that was the first time I had seen him so distraught. After that, it was just tragic, tragic. We tried to stay as close as possible as a family, but we weren’t always able to.”

The Colby family is well-known in Penacook and Boscawen. Merrimack Valley High School’s yearbooks are packed with their names. The Colby Tree Farm and Christmas Shop, run by Lynn and her husband, sit on 100 acres, with views of mountains and trees, and a landscape that seems to go on forever before a treeline far in the distance appears.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

N.H. Educators voice overwhelming concerns over State Board of Education’s proposals on minimum standards for public schools

N.H. Educators voice overwhelming concerns over State Board of Education’s proposals on minimum standards for public schools

“It’s beautiful” – Eight people experiencing homelessness to move into Pleasant Street apartments

“It’s beautiful” – Eight people experiencing homelessness to move into Pleasant Street apartments

Voice of the Pride: Merrimack Valley sophomore Nick Gelinas never misses a game

Voice of the Pride: Merrimack Valley sophomore Nick Gelinas never misses a game

Matt Fisk will serve as next principal of Bow High School

Matt Fisk will serve as next principal of Bow High School

Former Concord firefighter sues city, claiming years of homophobic sexual harassment, retaliation

Former Concord firefighter sues city, claiming years of homophobic sexual harassment, retaliation

A trans teacher asked students about pronouns. Then the education commissioner found out.

A trans teacher asked students about pronouns. Then the education commissioner found out.

Their house is rustic, with wooded floors and ceilings and glass encasements filled with photos and trinkets. Its beauty belies the pain that this family has endured, beyond what happened to Skipper.

His death rocked the family’s world. His sister, Kelly, was 12 when the fatal crash occurred. She later died from a drug overdose.

“The minute Skipper died,” Colby said, “that was it for Kelly.”

Colby’s mother died from hepatitis in 1957 at the age of 37, when all the kids were young. “Dad cried,” Colby said.

Colby’s eyes sparkled blue and smiled, and her face was framed by hair of shiny silver. She was upbeat, but her emotions got the best of her and spilled out as she spoke about Kingsbury.

That’s why she wanted to be heard. The alcohol-related deaths of underage drinkers this time of year will haunt Colby and her family forever. She worried that teens will act irresponsibly during prom or graduation and end up dead.

“Students have to realize that they are not invincible against alcohol-related crashes,” Colby said.

She knows and worries that partying high school students won’t heed her advice through the haze and euphoria of the independence they feel this time of year.

Some kids will be smart. They won’t drink, but if they do, they’ll take an Uber or a cab home. Or they’ll sleep at the host’s home once the music stops, awake with a hangover, and live another 60 years or so.

Others? Unfortunately, they may drink at a friend’s home, or in a secluded area, not often patrolled by cops. They’ll drive away, the next party waiting, maybe just a few miles away. It could be a fatal gamble that carries consequences far beyond the driver.

It doesn’t have to be that way, Colby says. Not around here. You can obey the law and not drink. Or, you can toss your car keys into a little basket near the front door, pledging to remain overnight.

It’s too early to detect what sort of influence Colby’s words might have on students. She hopes they listen to her. She hopes they can appreciate the ripple effect that’s created when someone dies tragically.

She lives it every day.

“This is about Skipper,” Colby said. “It’s about him and how good he was and how he lived. But it’s about more than that. It’s also about my father’s grief.”

With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer

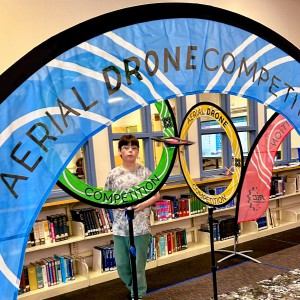

With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer Kearsarge Middle School drone team headed to West Virginia competition

Kearsarge Middle School drone team headed to West Virginia competition Phenix Hall, Christ the King food pantry, rail trail on Concord planning board’s agenda

Phenix Hall, Christ the King food pantry, rail trail on Concord planning board’s agenda