Granite Geek: The species preservation efforts around (checks notes) Edwards’ Hairstreak?

| Published: 05-24-2023 6:45 PM |

Today let us consider Edwards’ Hairstreak, which sounds like a mid-1980s glam band but is actually a butterfly with some weird aspects to its life cycle. It is of interest to us as Concord’s latest example of the indirect benefits that come from saving one little species.

As explained to me by Heidi Holman, the state wildlife biologist who runs the Karner blue Butterfly restoration project on the Army National Guard base next to Concord Municipal Airport, the Edwards’ Hairstreak is rarer than it seems like it should be.

This butterfly lives in scrub oak habitat found throughout the Northeast yet doesn’t thrive in much of them. However, it is doing OK in the Concord pine barrens that have been preserved to help the Karner blue, the state butterfly.

Why here and not elsewhere? This is a question that biologists associated with the Concord project are trying to answer, using expertise they’ve developed in two decades of supporting the Karner blue.

One way they’re doing this, Holman said, is by flagging ant nests at the base of mature scrub oaks. Edwards’ Hairstreak caterpillars live inside some anthills for protection; the ants put up with them because they eat the honeydew that the caterpillars secrete, even stroking them to encourage release of the sugar-rich, sticky liquid.

Maybe the Edwards’ Hairstreak is doing better in Concord because of something involving our ants. But all this happens out of sight inside anthills, so before biologists can delve further into the question , biologists first have to figure out how to observe and measure this insect symbiosis. Technology might help, although it might not.

“Supposedly they come out at night. We are looking at using black light which can help find caterpillars in the dark,” said Holman.

Maybe it won’t help but you don’t know until you try, which is exactly the kind of slow and tedious fieldwork required if you’re going to help species that are in trouble.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

N.H. Educators voice overwhelming concerns over State Board of Education’s proposals on minimum standards for public schools

N.H. Educators voice overwhelming concerns over State Board of Education’s proposals on minimum standards for public schools

Former Concord firefighter sues city, claiming years of homophobic sexual harassment, retaliation

Former Concord firefighter sues city, claiming years of homophobic sexual harassment, retaliation

Downtown cobbler breathes life into tired shoes, the environmentally friendly way

Downtown cobbler breathes life into tired shoes, the environmentally friendly way

Students’ first glimpse of new Allenstown school draws awe

Students’ first glimpse of new Allenstown school draws awe

Voice of the Pride: Merrimack Valley sophomore Nick Gelinas never misses a game

Voice of the Pride: Merrimack Valley sophomore Nick Gelinas never misses a game

A trans teacher asked students about pronouns. Then the education commissioner found out.

A trans teacher asked students about pronouns. Then the education commissioner found out.

During a short talk Friday as part of a celebration honoring this year’s50th anniversary of the federal Endangered Species Act, Holman pointed to the earlier examples of this slow but necessary work.

The Karner Blue project in Concord dates back to the late 1990s when the National Guard, which has been on the site in various forms since 1888, got together with the state and Concord to preserve the city’s section of pine barrens that had had hosted Karner Blue butterflies until they died out here some time in the 20th century.

Butterfly restoration work started by 2000 but even so, Holman said, it wasn’t until 2005 that they were able to start releasing some adults to repopulate the area. It took that long, she said, to figure out how to best bring populations from sites in New York state (is it better to carry eggs or fecund females?), how to raise them inside the bare-bones greenhouse on the National Guard property (what exactly do they eat at each stage of their life cycles?) and finally, where and when to release them on the property (when it’s sunny? when it’s windy? on which plants?).

More than 35,000 butterflies have been released since then but it’s an ongoing effort. Holman said the brutal drought of two summers ago clobbered the Karner Blues, forcing the project to import a couple thousand to restock the population. Another butterfly that is also dependent on the pine barrens, the frosted elfin, survived the drought just fine, providing another data point to consider.

Friday’s ceremony in Concord held on Endangered Species Day drew Kyla Hastie, regional director for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. In her remarks she celebrated how a multi-party cooperation that started as a focus on one pretty little insect has grown to help not just other species but other biologists, by passing along the protocols that they’ve developed through trial and error.

“They have expanded their scope, leveraged the knowledge to help other species around New England,” said Hastie. “This is a model of what we’re trying to do across the nation.”

With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer

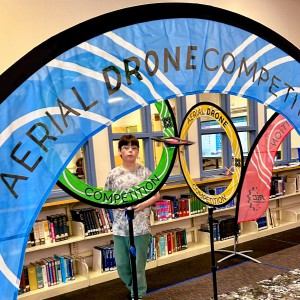

With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer Kearsarge Middle School drone team headed to West Virginia competition

Kearsarge Middle School drone team headed to West Virginia competition