She lost her son 150 years ago in the Civil War, and told a story of grief and sacrifice

| Published: 05-15-2023 7:30 PM |

Betsy Phelps had the eyes of a grieving mother this week.

Sometimes, she gave a warm and understanding gaze. Other times she just looked plain sad.

Never happy, though.

Phelps lost her son, Charles, at the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. She spoke to a small gathering in the lower level at the Concord Library, explaining her thoughts and feelings on outliving her child.

Phelps sprinkled in progressive ideas supporting equal rights for women, more than 150 years ago. And she used her platform to recruit for the war effort, laying foundations for volunteer programs designed to make Union soldiers as comfortable as possible.

“I’ll never forget the hymn they sang at the Congregational Church,” said Phelps, who was played by Sharon Wood of Claremont, dressed in the dress of the day, black as coal. “In the words of our pastor, Rev. Davis, he was a young man, but he was really an old soldier.”

Then, Phelps quickly and astutely changed gears, incorporating the many grieving mothers who had come to hear her speak, bringing them into an exclusive club, reassuring them that the hurt they felt was everywhere and that th eir feelings could be shared.

“Our story is not unique,” Phelps said. “It has been repeated many, many times in towns all over New England.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Wood the actor lives in Claremont. She wrote the script for the presentation herself. She’s been a librarian and calls herself a storyteller. She chose to recreate Phelps, a giant figure in American history who was way ahead of her time, who advanced her cause for women’s rights, even after her son’s death in the Civil War, and who became a hero in his hometown of Amherst after avenging the death of the beloved Col. Edward Cross.

Sometimes, Phelps’s husband, Steve, joins her at larger reenactments, playing President Abraham Lincoln and looking very much like him, even without his tall black stovepipe hat we’ve all come to know.

Steve was in attendance at the library this week, playing the part of himself. Meanwhile, his wife’s passion for what she does was obvious from her performance, coming just three days before Mother’s Day.

This was a dose of reality, reminding us what moms have had to face during wartime. In this case, Phelps continued her work trying to change an unfair society, at a time when many men did not want to hear it.

“Please forgive my boldness in standing before you this afternoon,” Phelps began her 45-minute speech. “We all realize it has long been considered improper for women to step into the world of public speaking. That belongs to men.”

She continued: “These are difficult times. The war has turned our lives upside down. Women have found it necessary to think and speak and act in the world in ways we never thought possible a few short years ago.”

Phelps recalled the day Charles left to fight the South. Many believed the war would last a few months. It lasted four years.

“The atmosphere was charged,” Phelps said. “The crowd cheering and shouting. There was pride in this mother’s heart at that moment, despite the fear that all mothers feel at such times. Of course, it was the same for you families, who sent your boys off to war .”

After Charles’s death, Phelps got busy. She created a network of sewers and knitters to add warm clothing to the soldiers’ lives. And they sent food. “Women in many towns cooked and packed a full dinner to send to our men,” Phelps said.

Roasted turkeys, a full pig, chicken, boiled ham, Plums, razors, soap, plums, pies.

During the first Thanksgiving of the war, in 1861, care packages stuffed with some of these meat items were sent to the “Boys.” But the boys received orders to move, and set up camp elsewhere. The goodies arrived in December. All the meat, of course, was spoiled.

“The boys even joked about giving the pig a funeral with military honors,” Phelps said.

An intimate question-and-answer session followed. Betsy Phelps turned back into Sharon Wood. She still looked the part, though, with black bonnet, black button-down vest, and a long black 19th-century Victorian dress, down to the floor.

It all seemed very real.

“It makes me so sad when I finish up here,” she said.

With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer

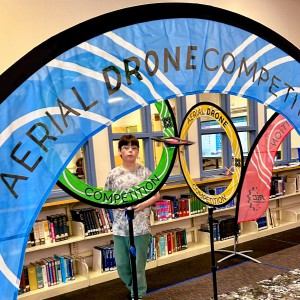

With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer Kearsarge Middle School drone team headed to West Virginia competition

Kearsarge Middle School drone team headed to West Virginia competition Phenix Hall, Christ the King food pantry, rail trail on Concord planning board’s agenda

Phenix Hall, Christ the King food pantry, rail trail on Concord planning board’s agenda Granite Geek: Forest streams are so pretty; too bad they’re such a pain to measure

Granite Geek: Forest streams are so pretty; too bad they’re such a pain to measure