John Broderick and Irene Buchine in Concord to Discuss Mental Health in Youth

| Published: 05-26-2023 3:48 PM |

John Broderick is accustomed to talking to children about youth mental health, but on Wednesday, it was the parents who listened.

Broderick relayed the words of a high school hockey player who confided in him: “I don’t think I ever had a childhood.”

“I did,” Broderick said to the audience. “And I bet you did, too.”

He gestured toward a couple, and they nodded.

Inside the Concord community center that evening, around 50 members of the community gathered around tables and engaged with mental health organizations. Outside, kids played soccer in the rain.

The event was called “What do I say? When do I say it?”. The speakers were Broderick, a former Chief Justice of the New Hampshire Supreme Court, and Irene Buchine, a children’s author and New Hampshire resident.

Both speakers have children who struggled with mental health growing up.

Broderick experienced a traumatic incident with his son years ago that taught him the importance of recognizing the signs of mental illness in children. “I have traveled now 100,000 miles in my black Jeep,” he said of visiting over 350 schools across the country to talk to kids and push for mental health awareness.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

No deal. Laconia buyer misses deadline, state is out $21.5 million.

No deal. Laconia buyer misses deadline, state is out $21.5 million.

“It’s beautiful” – Eight people experiencing homelessness to move into Pleasant Street apartments

“It’s beautiful” – Eight people experiencing homelessness to move into Pleasant Street apartments

With Concord down to one movie theater, is there a future to cinema-going?

With Concord down to one movie theater, is there a future to cinema-going?

Quickly extinguished fire leaves Concord man in critical condition

Quickly extinguished fire leaves Concord man in critical condition

Concord police ask for help in identifying person of interest in incidents of cars being keyed during Republican Party event

Concord police ask for help in identifying person of interest in incidents of cars being keyed during Republican Party event

Buchine raised a child with mental illness but didn’t know it at the time. “Ignoring it is the most dangerous thing you can do,” she said.

The country is experiencing a mental health crisis, especially its youth, Broderick said. He rattled off statics, like the rate of suicide for people ages 10 to 24, which he called “the wonder years of life,” increased 56% between 2007 and 2017.

Broderick’s speech focused on why this might be the case. His childhood, he said, was simple and pleasant. Nowadays, kids are “overachieving, overstructured, overscheduled.” They are absorbed by their phones which affects sleep and brain development. “Social-emotional growth happens eyeball to eyeball,” he said.

Throughout his speech, Broderick pleaded to the audience, “What are we doing?” He seemed to be desperate for action.

But Broderick is also hopeful about these kids. “They’re the least judgmental generation of Americans in the history of our country,” said Broderick. “They will talk about stuff that we never talked about.”

Andrew Heath, a coordinator at the Friends Program, represented one of the many community partners at the event. He struggled with his own mental health as a child and appreciated Broderick’s comforting demeanor.

“I wish I had someone like that when I was a kid,” said Heath.

Broderick’s speech was a dark reality check on the state of America’s children, but Buchine offered hope.

She laid out her own creative approach to combat the youth mental health epidemic. She wrote Celia and the Little Boy, a story about a boy hiding in darkness and a girl who tried to help him.

A large projector in the room displayed Celia and the Little Boy page by page, which was illustrated and narrated by Buchine.

“It was a warm book that did its best to talk about sort of a dark scary moment in youth depression,” said Heath.

When the event opened up for questions, the crowd took it as an opportunity for human connection.

One by one, parents stood up and shared stories of their kids’ depression, anxiety, misdiagnoses, and struggles to find therapy. As individuals revealed personal information, the rest of the audience nodded and Buchine responded.

Kiersty Scarponi, a licensed marriage and family therapist at the Concord Hospital Family Health Center, responded to a concern about kids bringing up big emotions close to bedtime.

“Our bodies are getting ready to go to sleep, so we’re vulnerable to feeling things in a heavy way,” said Scarponi, who suggested that parents keep a journal of their children’s intense feelings. That way, kids know that their parents take these thoughts seriously, and parents have time to process what their kids are telling them.

What parents understood in that room was the simple act of listening to one another’s troubles was comforting.

“When these parents are dealing with such an overwhelming issue, it can be easy to feel isolated and alone,” said Heath, reflecting on this moment of comradery.

The audience left with business cards, flyers, copies of Buchine’s book, and an understanding that other parents have children who are struggling, too.

Voice of the Pride: Merrimack Valley sophomore Nick Gelinas never misses a game

Voice of the Pride: Merrimack Valley sophomore Nick Gelinas never misses a game With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer

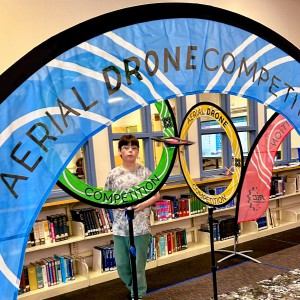

With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer Kearsarge Middle School drone team headed to West Virginia competition

Kearsarge Middle School drone team headed to West Virginia competition Phenix Hall, Christ the King food pantry, rail trail on Concord planning board’s agenda

Phenix Hall, Christ the King food pantry, rail trail on Concord planning board’s agenda